Cover image: Redaktsiya

On Saturdays I go to the Rock-Club

In the Rock-Club there are loads of good bands

They sing songs to me in my own language

I walk proudly with my ticket in my hand

‘The ordinary person’s song”, Mike Naumenko

2nd of October 2023. Rubinstein street, St Petersburg. A small crowd gathers outside number 13, an elaborate rose coloured building built in the 19th century. A purple curtain is pulled away to reveal a bronze plaque facing onto the street:

Photo: Dimitry Fufaev, Peterburgskiy Dnevnik

“Initially I was against this idea” says former secretary of the club, Olga Slobodskaya, to Bumaga.

“St Petersburg is a city with hundreds of memorial plaques. The majority of them were put up in honour of Lenin. These Leninist plaques did not stir up any positive feelings in us at the time of the Rock-Club. Plaques are as a rule, in honour of the dead. (…) When people ask, I always say that the Rock-Club dies when the last one of us dies.” (Bumaga)

The beginning

Today, 13 Rubinstein Street is a children’s theatre home to performers a world away from the “hooligans” and “delinquents” that treaded the boards 40 years ago. Its opening is a mythical event today. In Leningrad, local music enthusiasts had tried to open a rock club throughout the 70s. Before 1981 there had been Pop Federatsiya and Spektr, established by local musician Gena Zaitsev, but they were shut down by the authorities, as Vladimir Rekshan, journalist and musician explains:

“At the end of 1971, everything shut down. The musicians were called up by the Investigations Department, everyone was super afraid, but it became clear that these concerts were needed, a certain amount of concert organisers and spectators had been created. And the musicians wanted two things: applause and royalties, definitely not to overthrow the government. The rock club worked towards these aims” (Izvestiya)

Rock symbolised the dangerous influence of the West on the Soviet youth whose faith in the party line was decreasing year by year. The state approved alternatives were vocal-instrumental ensembles, who occasionally played on electric guitars with a sound close to rock, but this was not the same. The 1980 Olympic Games temporarily loosened the tight grip censorship had on Soviet artists, who used this oppurtunity to request that various independent youth clubs be set up for writers and artists, with music being the next logical step.

It’s believed that the initiators of the LRC’s creation was the local KGB, and that they decided to get all these underground musicians under one roof, so it would be easier to control them. But the initiative in fact came from below, and at some point the KGB realised that they was useful to them” – Artemiy Troitskiy, early advocate for rock music (Tass)

Censorship

On the 7th of March 1981 the first concert of the LenRockClub took place in the hall of the Leningrad Centre of Independent Arts. Bands who wanted perform there needed to pass a review in front of the committee headed by Nikolai Mikhaelov from 1982, the LRC chairman. Their lyrics also had to undergo “litovka”, a review process. Any lyrics that broke censorship laws would not only bring repercussions upon the performer, but also upon the rock club. Once checked, they would recieve a stamp of approval.

The rock-club in the 80s was not at all what we understand the word “club” to mean nowadays. It presented itself as a place to socialise, a place of contact between musicians. There was nothing else like it at that time… The censorship of lyrics, the so called “litovka” was an important aspect of our lives. The rehearsal team answered for this, headed by journalist Nina Baranovskaya. She was her own person in every way, she took charge of this duty because she knew the musicians and they trusted her. Thanks to Nina Baranovskaya, everything that the bands produced met the legal requirements. Each new band had to be reviewed by the LCR committee, which consisted of 5 people, including me. Since we were not Soviet bureaucrats, we kept a relaxed attitude, while still trying to observe the selection criteria. I remember Kino’s audition, which took place in a shared living complex somewhere in Avtovo, Leningrad. The band was still so young, and we really didn’t like them. But we let them in one of the festivals, they played, and everything went well. – Anatoliy Gunktsiy, founding member of “Aquarium”, poet and journalist, (Rokkult)

“For those bands that broke the rules, e.g, that sang the “wrong songs”, punitive action was taken by the rock club. They stripped these groups of the right to perform in other cities for three months and out of all the punishments they could have recieved, this was the most lenient. So the LRC protected and covered for its own” Vladimir Rekshan (Bumaga)

Tickets could not be bought and sold in the Soviet Union. Those who were club members, who knew the committee or were friends with the band performing that night could get a hold of tickets; everyone else crowded outside in the hope of getting in.

The sound quality left a lot to be desired, but compared to performing in your apartment or in someone’s basement, with the threat of your neighbours reporting you to the police for “hooliganism”, it was a dream come true. The Rock Club gave the bands a place to rehearse, perform and meet with likeminded people. Every year, around summertime, a rock festival was held there, during which popular bands presented a setlist of new songs.

KGB involvement

The Leningrad rock club gave us a chance to be noticed. We broke through the new generation of loyal party-liners and we had to get the rusty gears of party bureaucracy turning. At one point the phrase “red wedge” was actually commonplace, referring to DDT, Alisa and Televizor. They pushed us down, but we didn’t give in. Around 1986 Televizor was asked not to play two songs at the festival, which didn’t pass the litovka. There were two song lyrics that didn’t suit the big guys. But the setlist was ready and we decided to ignore their recommendation. They banned us for half a year, and then another six months because we played a few underground concerts despite the ban. – Mikhail Borzykin, Televizor, (Rokkult)

Testimonies like Borzykin’s speak to the club’s contentious history. It’s hotly debated to what extent the KGB were involved in its creation and management. Many point to the ex-head of the KGB, Oleg Kalugin, who wrote that it was created ‘to make it easier for the KGB and local government to manage what was going on in the alternative scene” (Mediazona). At one point band members had to visit KGB agents every two-three months for a “chat” where they would try to extract compromising information about other artists from them.

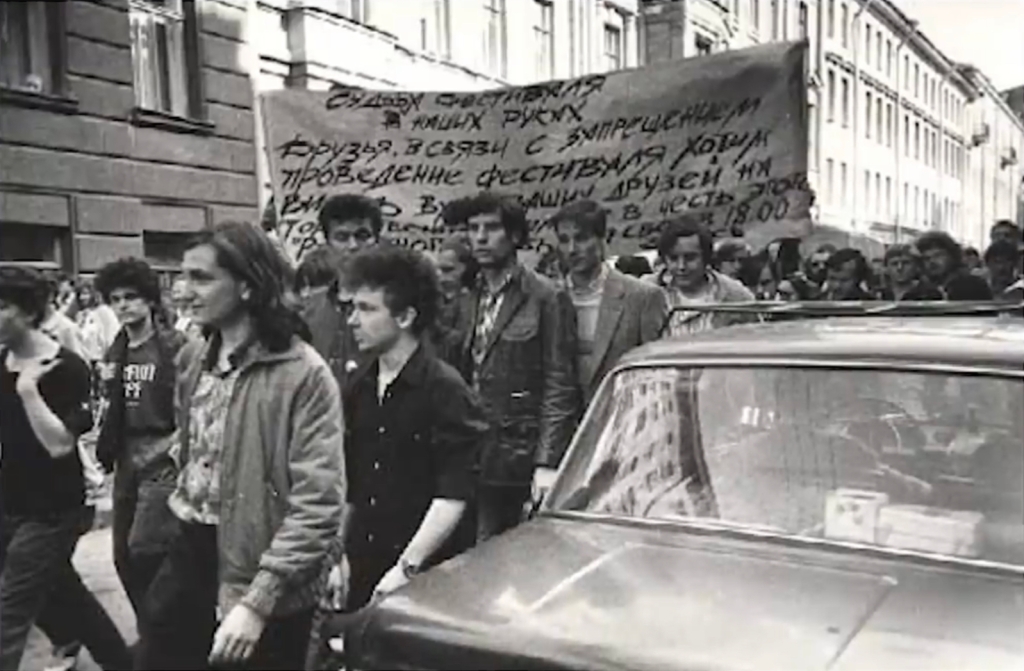

Even with the litovka, the artists could still land themselves in hot water for any careless comment. In one instance, Constantine Kinchev, frontman of Alisa, narrowly avoided jail after calling policemen “bastards” live on stage, a fate he only avoided, he says, thanks to the rock club committee. The festivals sparked media controversy each year, but 1988 was particularly memorable. Having had their festival cancelled at the last minute, rock fans, organised by Mikhail Borzykin, marched through Saint Petersburg and sat in front of the Leningrad cinema, refusing to move until the government agreed to negotiations. An agreement was reached between the LRC and the Leningrad authorities, and the concert went ahead.

In 1989, several spectators were arrested during an Aquarium concert including Aleksei Ipatovtsev, who was caught with a tape recorder in his bag and accused of illegally recording the concert to turn a profit. Fortunately, he was friends with Boris Grebenshikov, Aquarium’s frontman, who announced that the concert would not continue unless the police released the accused. A wave of chanting started up: “KGB out! KGB out!”. The undercover observers seemed to get the message, and soon enough almost a third of the seats in the hall were vacant. Then, as the now free Ipatotsev recalls “began the first ever free concert in my life. People were jumping on stage”. The artist in the wings came on to the stage and sang together with Aquarium frontman Boris Grebenshikov, who described feeling “this sensation that we had won in life, it meant an awful lot to us”. (Redaktsiya)

There were rock-bands who deliberately didn’t perform in the club. For some it was seen as a betrayal to have anything to do with the Leningrad Rock Club, viewed as an organisation that controls, while simultaneously involved with, rock-n-roll, the most liberated form of music. For punks to follow these rules was unthinkable.

Aleksei Pevchev, critic

The musicians were attention-starved, they desperately wanted to perform, and the LCR was their only oppurtunity. So with the choice between performing under the KGB’s roof or languishing in obscurity, it was completely obvious”. – Artemiy Troitsky

They didn’t come to any kind of compromise, they simply took advantage of the KGB’s fear, its paranoia and its determination to keep everyone under surveillance, including the spiritual and creative life of society and its people.

– Arthur Gasparyan, music editor for Moskovskiy Komsomolets

(The rock club) became the bridge that united us and the system, which allowed us to perform. But in my opinion, this came with a kind of surrender on our part. All the bands rewrote their works, they went through the litovka, each song recieved a stamp that read “approved for performance” and the rule breakers were reprimanded. They could control us, and creativity was no longer the only way the free spirit could express itself, but rather a part of the system. I am categorically against any form of structured organisation. Rock n’ roll is not structured. Rock music was underground, and in my opinion should have stayed there until the end, both during the ideological soviet system, and during capitalism, when stardom became tempting; even Aquarium, having become a megaband, started to play differently. So, if we need another rock club it must be different: no membership, no roll calls, no committee, no litovka.

Vsevolod Gakkel, member of Aquarium (Dzen)

Post-soviet era

In the Perestroika era, music in the Soviet Union changed dramatically. Bands who would never have dreamed of touring abroad were now jetting off to France, Germany and even America, usually advertised as an exotic novelty from behind the Iron Curtain. The bands that the LRC had helped to popularise were leaving it behind for the oppurtunity to play concert halls, and in rare cases, stadiums. The collapse of the Soviet Union spelled the end for the LRC, a non-profit organisation caught in a new mercantile era.

In the 90s the Leningrad Rock Club became less quaint, with all its odd rules about performing that we all chuckled at, but strictly followed nonetheless. (…) The rules disappeared, due to a more lax attitude which was growing in the country and the people were taking their rights back. People no longer performed in the rock club and began to fall away from this network because they could live more fully and freely. The newly published information about the KGB’s sponsorship did not win the rock club any points.

– Inna Volkova, singer (Russkiy Reporter)

For me this was a big mystery : They had so many connections across the country, in the touring industry, they could have become a powerful commercial organisation, and earned money. I think that the core team of the LCR committee were not ready to move to a for-profit path. New blood was needed, young specialists and managers. After the dawn of a new era of business and the removal of ideological restrictions the long-standing fallback that was the LRC was no longer necessary, and the bands jumped into the role of feisty modern commerical-organisers, working with the band management directly without any middlemen.

– Aleksei Pevchev (Tass)

(In the 90s) We moved to having two rooms, and it seemed to us then that our success would be unstoppable. In actual fact, we naively celebrated too early. The birth of cooperative-businesses resulted in the musicians going on tour around the country themselves and the middle man role which the rock-club had occupied disappeared. The managers at the time were not up to the new tasks.

– Vladimir Rekshan (Izvestiya)

The historical necessity of the Leningrad Rock Club with all its versatility fell away with time. We could have of course transformed it into a museum, like Vlad Rekshan is creating today, or thought up of something else, but we didn’t do this. We don’t have an exact date of when the rock-club closed, its work gradually came to a stop.

– Olga Slobodskaya (Bumaga)

Like Olga said, the legendary, controversial rock-club never officially closed ; the last attempt to revive it was a concert in 2016 featuring various classic Rock Club bands. A bronze plaque on a wall doesn’t really do justice to the thriving rock scene that the KGB tried to contain within these walls, but failed. These musicians were defined by their talent, their outrage, their unwavering determination. The rock club brought them under one roof, and cemented them in the memory of an entire generation and the generations to come.

Sources:

Maria Yakubova, (2016), Артемий Троицкий и руководители Ленинградского рок-клуба — о Цое, музыке 80-х и «аквариумской мафии, Bumaga, Accessed 14/04/24

Aleksei Pevchev, (2021), Музыканты хотели аплодисментов и гонораров, а не свергать власть, Izvestiya accessed 14/04/24

Kadriya Sadikova, (2021) Сюр, СССР и святая бюрократия. Музыкальные критики рассуждают о Ленинградском рок-клубе, Tass, accessed 14/04/24

Glukhov, D, Воспоминания участников Ленинградского рок-клуба, Rokkult – Dzen, accessed 14/04/24

Edward Andryushenko, (2020), КГБ‑рок. За созданием легендарного Ленинградского рок‑клуба стояли органы госбезопасности, Mediazona, accessed 14/4/2024

Redaktsiya (2019) How did Russian rock gain its freedom in 1980s? Accessed 14/04/24

Vsevolod Gakel, (2007) Если бы не было рок-клуба?, Spetsialnoe Radio accessed 14/04/24

Журнал Русский репортер — Expert.ru. Archived 13/12/2013

Leave a comment